-

Priscilla Rose Howe

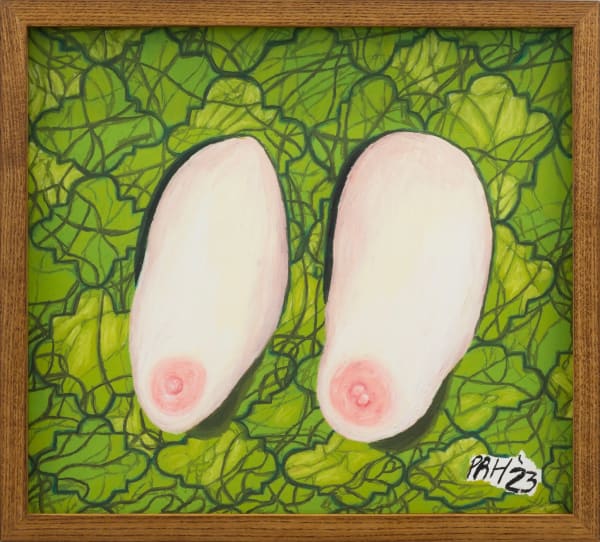

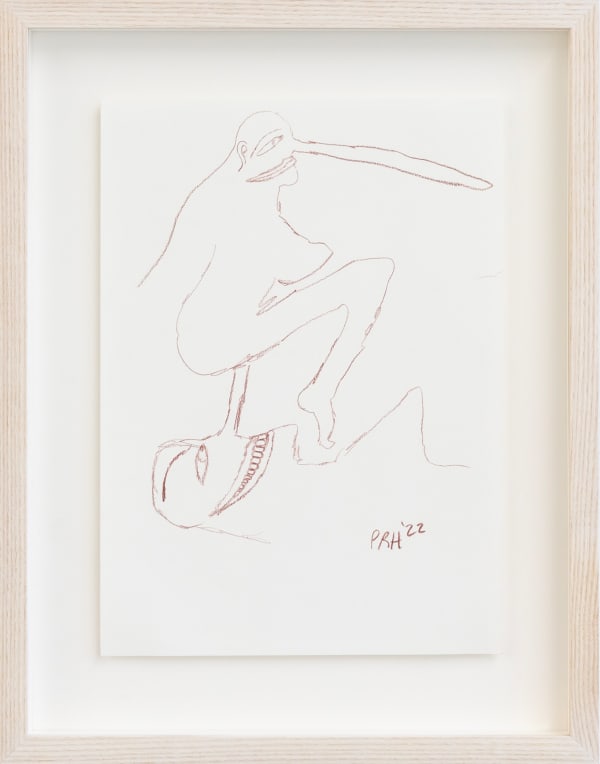

RoostingPriscilla Rose Howe is a Christchurch based artist whose pencil drawings might elicit descriptors like lewd, flowing, feathery, and femme. All of these would sit well, but neither do they fully qualify Howe’s cunningly flat missives which—if the viewer takes each composition’s silky invite to linger—gradually reveal themselves as spirited pieces of vaudevillian sexuality. The artist’s first solo show Roosting at Jhana Millers Gallery is no different, adding to a growing body of work that vibrates like a favourite sex-toy with fresh batteries.

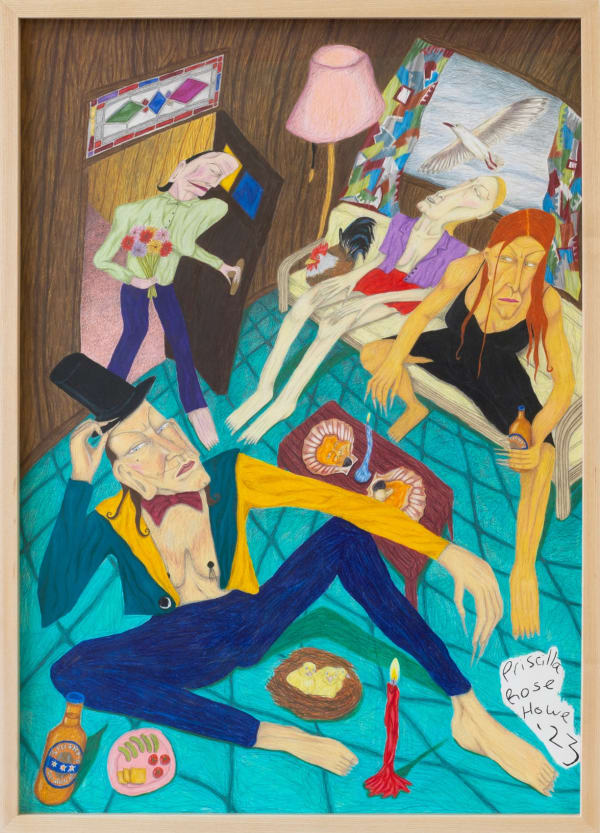

Howe’s tableaus have baroquely erotic charges that draw with lascivious glee on the whimsy of fairy-story illustration, like harems of Grimm-crones indulging sapphic (sabbath?) pleasures between moral fables, taking languid extended hiatus from conventional villainies for some vittles and puss. Top hats and vaudeville stripes aside, whimsy eventually exceeds spidery pictures from children’s books (most conspicuously, beloved Roald Dahl illustrator Quentin Blake) to echo the figurative traditions of other New Zealand greats like Rita Angus and Leo Bensemann; and then the artist goes further, catching these drifts only to bend them into enclaves of female supremacy, female carnality, a fecund utopia enshrouded in heavy velvet drapes and tobacco smoke, the air as thick with alcohol as it is sex and food. Arguably mirroring the male-only fantasias of gay sexual utopianizing (cruise clubs, men’s saunas etc.), Howe’s figures carry their own masculine swagger and show sexual difference in grubbier, muscular spectrums of womanhood. Like burlesque amazons who’ve been around the block a few times and know the true spiritual significance of feasting. Seasoned oracles at a Delphi tavern.

If Howe’s work has a throughline it is this notion of feasting, the intimate Mardi Gras, sex as connective tissue. The community-building ethos of regular orgies. Where the chicly self-possessed (the glamorous) might gather without touching, Howe’s figures have little driving them but the agency of desire, their protruding noses a burning phallus which no program of feminine presentation can persuade them to camouflage; these ladies wear their hard dicks proudly. Conventional beauty, then—perhaps especially in a climate of propulsive self-aggrandizement and curated self-surveillance—gives off an iciness, a calculating deployment of physical perfection running conspicuously cold. Almost in rebuttal to the isolated figure as some litmus of modern romance in decline, Howe’s schemas are revels, the prospect of physical intimacy not just attainable but mandatory within these gatherings which are as much about kinship as they are satiation. Their harkening to illustration then, the cosmetic story-book innocence of pencil-drawings, is arguably more to do with reinstating pleasure as the primary directive, where for too long more ideological descriptors have dominated queer rhetoric. It’s dissolution (disillusion?) of theoretical knottiness through sex, through food, through touch. The isolation of perfection is here rejected for a twilight return to the mythopoetic bacchanal.

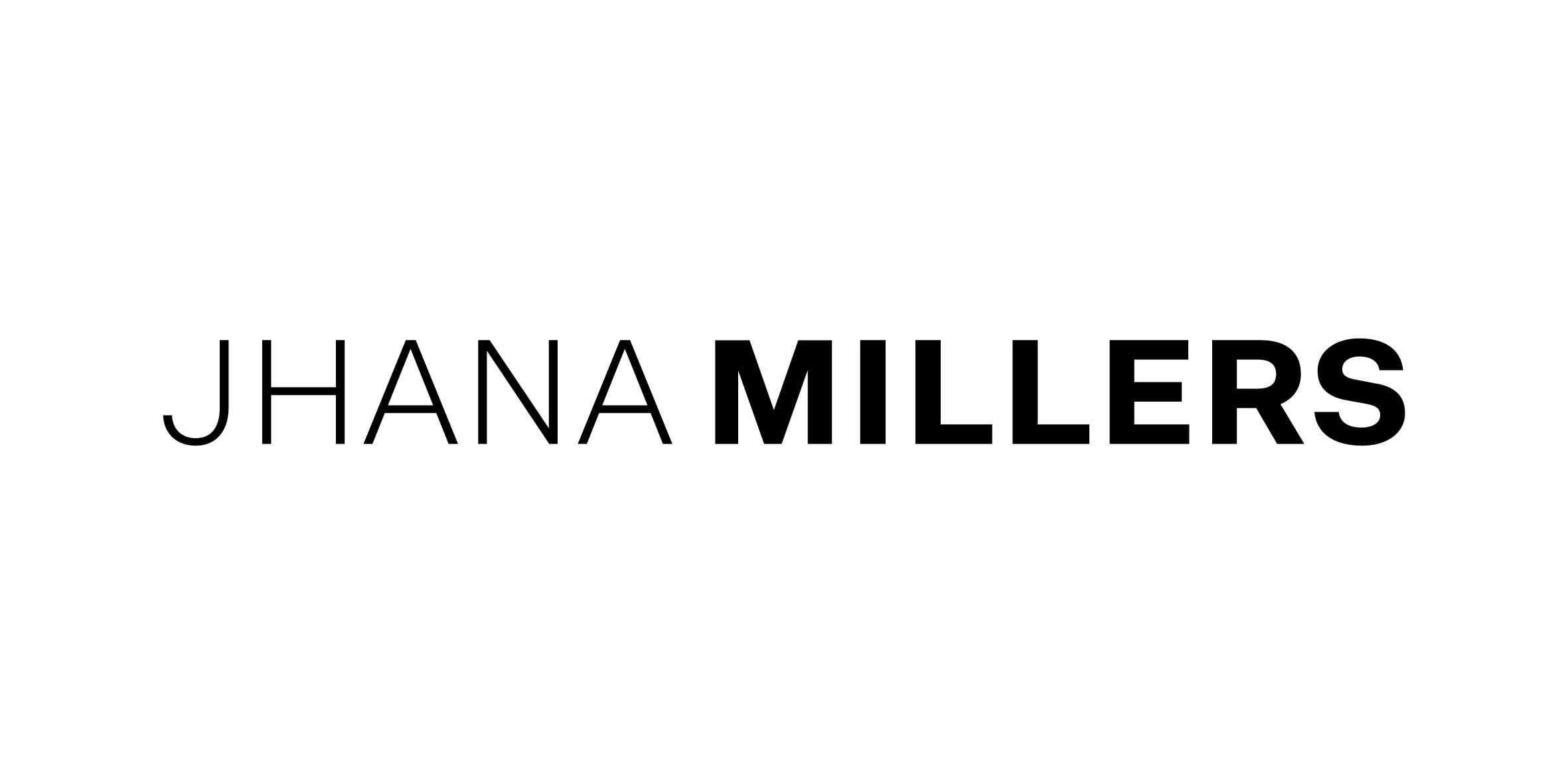

The gloryhole is a traditionally masculine adventure; for the uninitiated, a gap between public toilet stalls for a man to stick his cock for some anonymous head. In the hands of Priscilla Rose Howe—and an overt reference to the same motif in John Waters’ film Desperate Living—the gloryhole is reclaimed for breasts and the female silhouette, folded into the artist’s greasy-chinned sapphic utopianism as seamlessly as a double-ended dildo. It’s like the apotheosis of Howe’s phallic noses, the phallus blooming in less conventional gardens. There are even allusions here to Pinocchio in his pursuit of authenticity (please make me a real boy, bartering with an indifferent creator), except these lascivious crones bypass the need of Blue Fairy’s wand waving and content themselves with protruding deceptions (tell a lie, watch it grow). But one man’s lie is another man’s fantasy. In the magic circles of Howe’s compositions the lines between fact and fantasy are alluringly porous, and anything (bodies, flavours, positions, staminas) can be spoken into being. Like the gloryhole itself Howe’s gatherings occupy liminal space, the spectral nowheres queering neglected potentials in-between; pastures which would otherwise be cultivated in normative sprawls but for their geographical (and sexual) elusiveness. It’s difficult to market the improvisational tone of the truly liberated. It has to be experienced directly or not at all. How then do you sell the cascading slippage of change if you can’t slow bodies down enough for a commercially viable shot? Perhaps this is why Howe’s figures defy generic proportions, their warping not so much a lack of finesse as the happy symptom of its conscious rejection. Formalism and appetite are uncomfortable bedfellows anyway. Loin and belly heat disfigure anything that comes too close to it. Straight lines mellow like glass in a kiln.

Even if just a sketch of an ideal it’s clear Howe’s fixations grip the prospect of more emancipated living, a concealment of rabid dreaming; a welcome relief from the refrains of contemporary artists shrouding skeletal work in the security of political registers. Rather than explain away sex in grids of inequity and performance, the artist reaches instead for the primacy of bodies, for languages more closely skirting the unconscious and its guttural-gestural expression; so often sneaking in between what we intend to say, never the thing perfectly executed but always the thing that’s on fire. As a solo showing, Roosting points to the beginning of a ride as hot as it is long and hard.

Sam te Kani, 2023

Priscilla Rose Howe, Roosting: Viewing room

Past viewing_room