Ayesha Green, Good Citizen

Ayesha Green’s solo exhibition Good Citizen operates at the intersections of culture, religion, whakapapa and nationality. In this new suite of portraits and works on paper, Ayesha asks, what might good citizenship be? Who gets to define what is good and who gets to define what it might mean to be a citizen? Within a nation-building framework, Māori are forced to perform their citizenship through acts of assimilation. In this exhibition, Green specifically explores the interracial family unit and how this process has resulted in her own identity as a citizen of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Good Citizen is grounded in the religious allegory of Mary mourning over the body of her dead son, Jesus. This iconic image provides a critical entry-point with Mary’s role as a cipher, deployed as the perfect feminine image of deference, sacrifice and ultimately, unattainability.

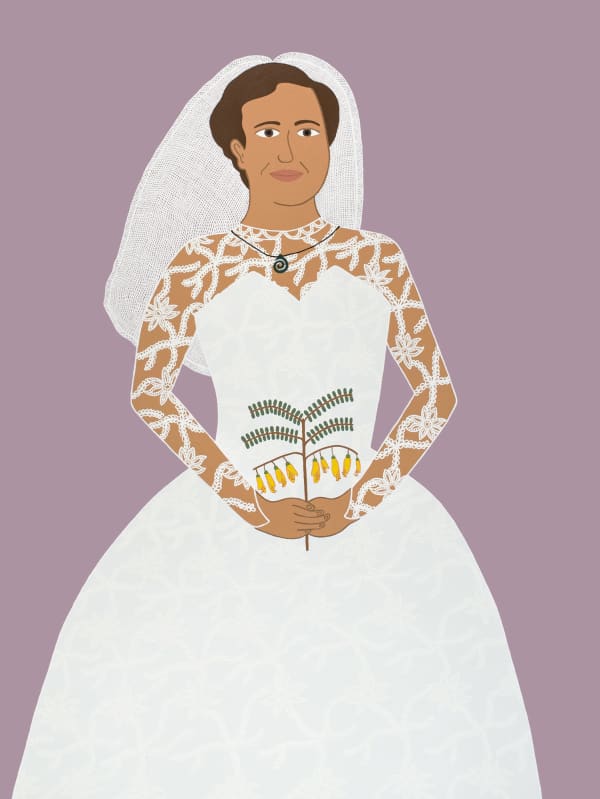

Botanical patterning is used to echo the unending nature of whakapapa and its connection to Papatūānuku, travelling through images of Green’s grandmother, mother, and herself. These portraits of an artist and her whānau wāhine draw parallels between the self, intermarriage and ‘successful’ assimilation.

Extract from the essay, The Inalienability of Whakapapa, by Matariki Williams (Tūhoe, Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Hauiti, Taranaki). Read it below.

Ayesha Green (Kai Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu) is an artist based in Tāmaki Makaurau. She graduated with a Bachelor of Media Arts from Wintec in 2009 and went on to complete a Master of Fine Arts from Elam in 2013. In 2016 she completed a Graduate Diploma in Arts specalising in Museums and Cultural Heritage. In 2020 she was a Springboard Arts Foundation Recipient and in 2019 she won the National Contemporary Art Awards. Recent exhibitions include: Toi Tū Toi Ora, Auckland Art Gallery 2020/21, Wrapped up in Clouds, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 2020, Strands, The Dowse Art Museum (2019); Tuia — Southern Encounters, The Hocken Gallery (2019); Elizabeth the First, Jhana Millers. Her work is in the collection of Te Papa Tongarewa, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, The Dowse Art Museum, The Govett-Brewster, The MTG Hawkes Bay and more.

-

Ayesha Green, In the beginning, 2021

Ayesha Green, In the beginning, 2021 -

Ayesha Green, Nana on her wedding day, 2021

Ayesha Green, Nana on her wedding day, 2021 -

Ayesha Green, Mum on her wedding day, 2021

Ayesha Green, Mum on her wedding day, 2021 -

Ayesha Green, Ayesha, 2021

Ayesha Green, Ayesha, 2021 -

Ayesha Green, My mother (thinking of the horizon), 2020

Ayesha Green, My mother (thinking of the horizon), 2020 -

Ayesha Green, Passport #1, 2021

Ayesha Green, Passport #1, 2021 -

Ayesha Green, Passport #3, 2021

Ayesha Green, Passport #3, 2021 -

Ayesha Green, Passport #2, 2021

Ayesha Green, Passport #2, 2021

The Inalienability of Whakapapa

Matariki Williams (Tūhoe, Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Hauiti, Taranaki)

Prior to the coming of the Pākehā, citizenship was arguably not a concept exercised in Aotearoa. Rather, societal groupings were understood via whānau, hapū, iwi, and the many connections therein. Through Te Tiriti o Waitangi, citizenship was explicitly guaranteed to Māori by Queen Victoria in 1840 via Article Three. In this article, and as part of the governance arrangement signed to with Māori, the Queen of England afforded to Māori all the rights and duties of citizenship as the people of England. This article came after the preceding two articles which had awarded governance of the country to the Queen, and crucially retained “te tino rangatiratanga o o rātou whenua, ō rātou kāinga, me ō rātou taonga katoa.”

This line will remain untranslated in this text for two reasons. Firstly, Māori and Pākehā perspectives on our founding document have been lost in translation since the 1840 signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The extent of this continues to this day where Māori claim that sovereignty was never ceded, rather only governance was. Consequently we must advocate for iwi, hapū and other grouping rights through the Waitangi Tribunal. As has become apparent over the subsequent 181 years since the signing, discrepancies in the wording in te reo Māori and English has contributed to a fraught expression of citizenship for Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. To translate is to lose meaning. Secondly, this holding of space, and claiming of a sovereign right to determine interpretation is evident throughout the work of Ayesha Green (Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu).

Operating at the intersections of culture, religion, whakapapa and nationality, Green’s Good Citizen compels viewers to consider what citizenship has required of Māori. How does the promise of tino rangatiratanga manifest for Māori when our land, homes, and taonga, that are crucial to our culture, are taken from us? How can the privileges of citizenship be enjoyed whilst attempting to also maintain a self-determining idea of cultural identity?

To find answers, Green has taken a micro-historical approach, entering these narratives through her whānau kōrero wherein citizenship is linked to the subversive acts of government- mandated assimilation. Green takes the religious allegory of Mary mourning over the body

of her dead son, Jesus, as an entry-point to the way in which Christianity was enacted in Aotearoa. Here, Mary’s role was as cipher, deployed throughout Māori girls’ boarding schools as the perfect feminine image of deference, sacrifice and ultimately, unattainability. Mary’s unattainability echoes the incongruous ask of Māori to be both self-determining, and to conform to the structures of settler-colonial governance. The historical focus on domesticity from these boarding schools is something Green sees play out within her own whānau where the ideal was to marry non-Māori in order to have access to the best out of life.

In her passport paintings, passports being the ultimate symbol of citizenship in their granting of inalienable admission to countries, Green’s use of kōkōwai from Karitane subverts a

government-prescribed definition of access to land. The te reo Māori terms used in this official document (iwi tūturu for nationality, and uruwhenua for passport) further illustrate the duality of Green’s identity as Māori in New Zealand. Iwi tūturu can be interpreted as being of an iwi that were original inhabitants of a place or those who can make claim to a place. Uruwhenua refers to the granting of access into a country but here is specifically saying whenua, a word that bears much more weight to Māori than ‘land’.

In this suite of works we see Green’s idiosyncratic use of botanical representations which connect these portraits to one another. The tessellating patterns within these portraits echo the unending nature of whakapapa that travel through images of her grandmother, mother, and herself. As accumulations of those who have gone before, these portraits of an artist and her whānau ask, where does the ‘I’ begin, where does the ‘they’ end? So too could viewers consider the adornment of a pounamu necklace and its recurrence in multiple works, is this a symbol of endurance against the odds of a stultifying colonial project or the recognition of whakapapa in and of itself?

Whakapapa, as a holder of loss and connection is more visible to me in Green’s work than citizenship. One reason could be because grief is present in its expression, from the mourning figure of In the Beginning to the contemplative My mother (thinking of the Horizon) who is considering a different future to what she finds herself in. Citizenship is about a belonging that is written into official documents where whakapapa can be much more complex and loaded with pain. Whakapapa should have been inalienable for Māori but the reality is that disconnection is just as present for some Māori as whakapapa. The inter-generational accumulation of how whakapapa has been interrupted is present throughout Green’s work, and yet so too is her rangatiratanga over the gaze that deigns to define what this looks like.