Priscilla Rose Howe, Rabid

Priscilla Rose Howe’s drawings are obscene. Her work depicts a universe of apocalyptic pageantry, rendered in coloured pencil. Ribcages open like altars, meat floats like relics, and matriarchs leer over butchered pigs in domestic spaces warped into sites of ritual and rupture.

Howe’s aesthetic is low-budget and high-intensity—part Troma gore, part John Waters camp. Her images warp femininity, religiosity, and home life into grotesque theatre. The result is a kind of psychic autopsy: part shrine, part punchline. There’s no clean narrative here, no moral lesson—just ecstatic disorder.

Executed in slow, scratchy pencil, these drawings are painstaking acts of desecration and devotion. In Howe’s hands, the pencil becomes both scalpel and wand, cutting and conjuring. Her bodies are not whole, nor do they aspire to be. They sprawl, grin, ooze, and glow. The violence is visible, but so is the humour. Through absurdity and excess, Rabid seeks revelation.

This is mysticism by meat tray—a theology of the broken, the defiled, and the divine. A lipstick smile. A halo of ribs. A sofa soaked in vomit and roses. The familiar is rendered strange, and the strange, sacred.

In a culture where repression and respectability often go hand in hand, Howe’s work leans sideways. It refuses good taste, coherence, and control. Instead, it offers something more unruly: a cracked kind of spirituality, where queerness, trauma, and laughter are part of the same ritual.

The above was adapted from the exhibition text Tuatua Soup by DJCS, written to accompany the show.

Tuatua Soup

DJCS

1 quart of milk

½ lb. minced tuatua

salt + pepper

Put on + bring to boil

In a separate saucepan mix 7 level tablespoons of Oyster Chowder to a smooth paste with cold water. Add 1 quart of boiling water + bring to the boil. Add to milk mixture. Colour (Slightly) with green food colouring.

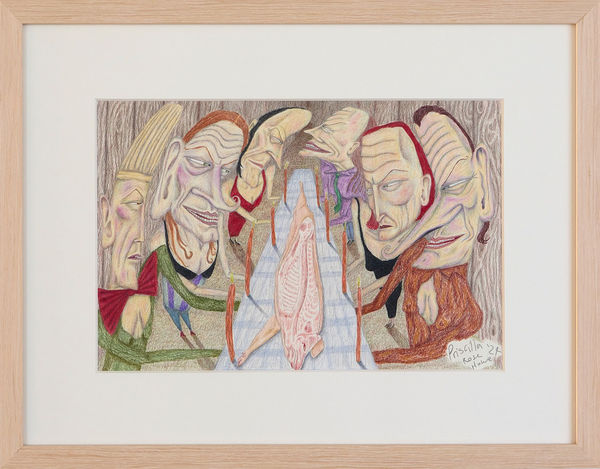

Priscilla Rose Howe’s drawings are obscene. Her work depicts a universe of apocalyptic pageantry, rendered in coloured pencil. A smiling figure reclines across a crummy floral couch beneath a row of fossilised jawbones; a table of ghoul-faced matriarchs gather over a butchered pig; a figure spreads themselves wide, ribcage open to the heavens, surrounded by chunks of meat. The drawings are psychic autopsies. Portals.

Howe’s aesthetic is low-budget and high-intensity. Like the palette of a Troma Entertainment film, or the trash-camp of John Waters, Howe’s drawings refuse good taste in favour of something more potent. They operate through what theorist José Esteban Muñoz might call disidentification, a queering of cultural tropes through exaggeration and mutation. Her drawings warp femininity, domesticity, and religiosity.

The Troma lineage is especially resonant. In Tromeo and Juliet (1996), Shakespeare’s tragedy becomes a carnival of incest, punk aesthetics, and low-res gore. What’s compelling is not just the outrageousness, it’s the way Troma weaponises failure as style. Narrative coherence collapses. Production values disintegrate. What emerges is a theatre of negation: a refusal to be respectable, clean, straight.

Howe’s drawings operate similarly. Organs, ribs, and vulva are flayed open in a pose somewhere between religious martyrdom and pornographic spectacle. The figure is framed like a stage, surrounded by floating cuts of meat, like holy relics or supermarket bargains. It is part shrine, part punchline.

The drawings do not ask for empathy, or moralise. They offer something closer to Genesis P-Orridge’s concept of “cut-up identity” - the self as a collage of meat, symbol, ritual, and kink. In this context the body is sacred precisely because it is fragmented, defiled, and absurd. Howe’s practice is mysticism by meat tray.

It’s important to acknowledge that Howe’s works are made in pencil. Meticulous, scratchy, slow. Pencil is not a medium of speed or spontaneity. It requires attention, repetition, and has a possibility for erasure. In Kabbalistic thought, the concept of the ‘shattering of vessels’ describes the moment when divine light could not be contained by its appointed forms, causing a cosmic rupture. Howe’s pencil drawings enact this theology. Each form acts like a vessel under pressure, straining to hold its meaning. But the vessels break, and what pours out is laughter, blood, queerness, meat.

Drawing, for Howe, is an act of cosmological disorder, a reconfiguration of symbols we thought we understood. The kitchen becomes a crime scene. The body becomes both altar and abattoir. The dinner table becomes a tribunal of leering, misshapen elders. Her pencil operates as a scalpel and a wand, carving and conjuring.

In Aotearoa, where respectability and repression often operate hand in hand, especially across the axes of class and gender, Howe’s drawings act as an ungluing of the nation’s interior logic. The domestic spaces she depicts are deeply familiar - the couch is floral, the curtains are laced, the room is carpeted in a scratchy 70s red. A reclining figure wears a red and black lingerie set, their smile stretched too wide. Behind them, three jawbones hang like trophies. What kind of family lives here? What is being consumed?

There’s a deep critique of patriarchy embedded in these works through structure and affect. A row of grotesque women - part judge, part puppet, part corpse - recalls a boardroom, a church committee, or a meat market auction. The central pig, bisected and splayed, becomes a surrogate for the absent body, or perhaps the body as it is always seen under patriarchy: consumable. Yet, the pig glows. It anchors the scene, inviting horror while compelling attention. There is power in refusing to look away.

The brilliance of Howe’s work lies in its ability to oscillate between trauma and camp, between sacred and absurd. The work seeks revelation through exposure. By making the violence visible, by restaging the theatre of gender through absurdity, Howe opens up a different kind of spirituality. A cracked one.

These drawings revel in the aesthetics of poor taste as a tactic. As a way of resisting the smoothness of capital, the clarity of binaries, the demand for resolution. In doing so, they produce a space for what Sara Ahmed calls ‘queer orientations,’ bodies that lean sideways, break rhythm, and refuse the straight line. In this sense, Howe’s drawings are profoundly hopeful. Not because they depict hope, but because they reject the lie that things were ever whole to begin with. They offer the sacred in shards. A rib cage halo. A sofa covered in vomit and roses. A lipstick smile.